Vemo HBOT Video and Agostini Photography get it

August 30, 2020

Dr. Paul Harch in NYC at The Lost Corvettes Giveaway

May 30, 2021Research News and Some Surprising Findings

by Drs. Susan Andrews and Paul Harch

Psychology Times, October 2020 – Science & Education – Page 10

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy chamber being used by Navy personnel. (courtesy photo, US Navy)

After completing our 10-year research project on the effectiveness of treating mTBI, Persistent Postconcussional Syndrome (PPCS), and PTSD with Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT), we (Susan Andrews, PhD and Paul Harch, MD) published the major findings in Medical Gas Research1 in the March 2020 issue.

Dr. Harch, an acknowledged world leader in hyperbarics, in the Department of Medicine, Emergency and Hyperbaric Medicine Section, LSUHSC in New Orleans, conceived of the study, registered the study with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and was responsible for obtaining funding2.

Neuropsychology played a major role in gathering the outcome data to show how HBOT improves cognitive function even in the chronic phase of mTBI patients. It is our hope, Dr. Harch as the principal investigator and Dr. Andrews as the neuropsychologist, that HBOT will soon become more available as insurance and Worker’s Compensation groups begin to approve it.

There are many important findings from the long-term study reported in the Medical Gas Research publication. However, for this news article, we want to focus on some of the findings that were surprising and particularly relevant to psychologists.

It’s time to rethink our definition or basis for “deficit.”

One of the most important findings from the two studies actually challenges a fundamental principle or standard upon which the entire field of neuropsychology has relied. In order to diagnose a Neurocognitive Disorder, neuropsychology relies on finding “cognitive deficits.” In fact, the DSM 5 diagnostic criteria require: 1) evidence of significant cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (such as, memory, attention and concentration or executive function) or 2) a substantial impairment in cognitive performance, preferably documented by standardized neuropsychological testing. Deficits have traditionally been operationally defined as a T score below 40, which is equivalent to a standard score below 85. If literally followed the first criteria is difficult to satisfy since neuropsychologists rarely have premorbid comparison testing, and the second criteria is only achieved for the more severely injured. From the perspective of a referring clinician this is the biggest problem when they receive a report after referring a patient for neuropsychological testing. The recruited subjects in the first phase of the research included 30 military veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan Wars with mild TBI and Persistent Postconcussion Syndrome (PPCS).

Many of these men also suffered from PTSD and depression. In the second phase experiment, 50 military and civilian subjects with mild TBI and PPCS completed the full protocol (23 in the HBOT group and 27 in the Control Crossover Group that also received HBOT). The FDA required that we screen out active PTSD in the second phase of the study and stratify the two groups for amount of depression. The recruited subjects came in complaining of continuing cognitive problems, depression and anxiety, and postconcussion symptoms. They all reported that they were not completely “back to their normal” (pre-injury level) from before they were injured.

Once recruited, all subjects received a full battery of neuropsychological tests before and after treatment with hyperbaric oxygen therapy, including measures of IQ, learning and memory, measures of complex attention, executive function, language, perceptualmotor function, depression, anxiety, sleep, and Quality of Life.

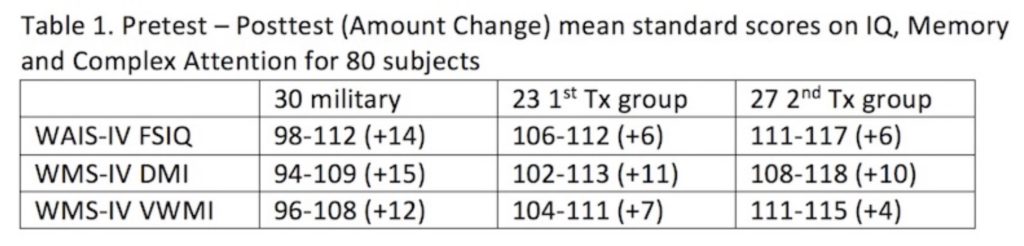

The first surprise was that the baseline testing revealed that most of the subjects were essentially “average” – not deficient – in the bulk of the cognitive domains tested (see Table 1). The mean scores before treatment ranged from 94 for delayed memory for the 30 military subjects to 111 on Full Scale IQ and Visual Working Memory Index for the Phase II Control Crossover group. In fact, had these subjects been tested before they were recruited, most of them probably would not have been included in the study by the current definition of deficit or impairment.

Even more surprising was how much each group gained in standard scores after the hyperbaric oxygen treatments (full protocol of 40, 1 hour treatments).

The biggest cognitive gain was seen in the Delayed Memory Index (DMI) from the WMS-IV across all three sets of subjects who received HBOT. The military subjects showed the greatest gains, however, most of the military subjects experienced blast concussions compared to blunt concussions of the mostly civilian two groups in the Phase II research. In addition, many of the military subjects had experienced more than one such concussion, and also had PTSD scores 50% higher than the Phase II subjects. The military gains were almost a full standard deviation, while the civilian mTBIs each gained 10 to 11 points into the High Average range and generally reported that they felt more “back to their preinjury normal.”

When the data from the first experiment with military subjects was first published in 20113, there was a letter to the Editor by Wortzel et al4, who commented that our neuropsychological improvements were “dramatically larger than can be explained.” This comment was apparently based on the fact that the literature shows no decrement in intellectual functioning following mild TBI5. However, it has now been demonstrated in multiple Department of Defense (DoD) HBOT TBI studies that the comorbidity of PTSD amplifies the improvements seen with HBOT in TBI. Our military subjects had the highest average PTSD score of all of these studies, nearly 50% higher than the DoD subjects.

We recognize that it has been considered a “fact” that IQ is not usually affected by mild TBI. However, the data disputes that “fact.” One reason for why it seems that IQ is not affected by mTBI is that most neuropsychological data is generated after an injury and there is often only one time point tested. Improvement can be seen occasionally when two time points are available (like relatively soon after the accident and one to two years after the brain has had time to recover.) In addition, large decrements in global intellectual function, i.e., IQ, that falls outside the “normal” range, are only likely to be seen in more serious injury.

People who have been injured often complain of not being “back to normal.” However, if their IQ or memory or attention is in the normal or average range when tested, the subject is not considered to have a loss of function. This often leads to the injured person’s complaints not being considered valid and therefore, they often do not receive the treatment they actually could still benefit from. One implication for the future is that some good way of determining “back to normal” needs to be considered.

Post-Concussion Symptom Inventories are Good Predictors of Outcome

The FDA required the use of the Neurobehavioral Symptom Inventory (NSI), which is a post-concussion symptom inventory, as our primary outcome measure for the second phase of the experiment. Two of the largest improvements for the subjects were on the NSI and memory. There was a huge decrease in headaches for the group receiving HBOT. The study demonstrated an approximately 85% improvement in headache, along with improved sleep, energy level, irritability and mood swings. Headache is one of the most debilitating post-concussion symptoms that often keeps people from being able to return to work.

At the time of the first phase of this research, many of the returning Iraqi and Afghanistan military were so distressed that they were committing suicide. A very important finding of the Phase I study was a significant reduction in suicidal ideation among the subjects.

Beyond the surprising findings of “deficits” in the “normal” range, increases in “from an Average IQ to a High Average IQ or more”, a major reduction in suicidal ideation, and greatly improved Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and anxiety, the important conclusion was that this study confirmed 30 years of animal and human experience, demonstrating significant improvement in PPCS with the 1.5 atmosphere oxygen dose. This dose of HBOT has been applied in multiple other randomized trials with similar results. Collectively, the body of data meets criteria for American Heart Association Level I Class A evidence for efficacy of HBOT in mTBI PPCS. It is now time for widespread application of and reimbursement for HBOT treatment of mTBI PPCS with or without PTSD.

Dr. Harch as the principal investigator and Dr. Andrews as the neuropsychologist, hope that HBOT will soon become more available as insurance and Worker’s Compensation groups begin to approve it.

1 Paul G. Harch, Andrews SR, Rowe CJ, Lischka

JR, Townsend MH, Yu Q, Mercante DE. Hyperbaric

oxygen therapy for mild traumatic brain injury

persistent postconcussion syndrome: a randomized

controlled trial. Med Gas Res. 2020; 10 (1): 8-20.

2 This study was supported by U.S. Army Medical

Research and Materiel Command Fort Detrick, No,

No. W81XWH-

3 Harch, Paul G., Susan R Andrews, Edward F.

Fogarty, Daniel Amen, John C Pezzullo, Juliette

Lucarini, Claire Aubrey, Derek Taylor, Paul Staab,

and Keith Van Meter. (2011). A Phase I Study of

Low-Pressure Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Blast-

Induced Post-Concussion Syndrome and Post-

Traumatic Stress Disorder. Journal of Neurotrauma,

28-1.

4 Wortzel et al. (2012). A Phase I Study of Low-

Pressure Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Blast-

Induced Post-Concussion Syndrome and Post-

Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Neuropsychiatric

Perspective. J of NT, 29-14.

5 Belanger et al., 2005 (a meta-analytical study that

could only report general findings across nine

cognitive domains.)