Dr. Harch’s groundbreaking research using hyperbaric oxygen to treat Alzheimer’s dementia was published today. Thank you for being supportive of Dr. Harch and his work.

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Making Kids Happy

November 11, 2018LSU Alzheimer’s treatment shows promise: Interview with Dr. Harch

January 31, 2019Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for Alzheimer’s dementia with positron emission tomography imaging: a case report

[stm_post_details]Abstract

A 58-year-old female was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) which was rapidly progressive in the 8 months prior to initiation of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). 18 Fluorodeoxyglucose (18 FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) brain imaging demonstrated global and typical metabolic deficits in AD (posterior temporal-parietal watershed and cingulate areas). An 8-week course of HBOT reversed the patient’s symptomatic decline. Repeat PET imaging demonstrated a corresponding 6.5–38% regional and global increase in brain metabolism, including increased metabolism in the typical AD diagnostic areas of the brain. Continued HBOT in conjunction with standard pharmacotherapy maintained the patient’s symptomatic level of function over an ensuing 22 months. This is the first reported case of simultaneous HBOT-induced symptomatic and 18 FDG PET documented improvement of brain metabolism in AD and suggests an effect on global pathology in AD

Introduction

The prevalence 1,2 and costs 2 of dementia, of which Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) 3 is the dominant subtype, are substantial. 3 AD is characterized by deficits in memory and executive function. 4 Treatments have focused on pharmacotherapy, 5 but from 2002–2012 the US Food and Drug Administration has cleared only 1 of 244 drugs tested 6 and no therapy halts disease progression. 7 The dual-drug hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) 8,9 has many neurological applications. 10 The first successful HBOT treated case of AD was published in 2001. 11,12 The present case report is the first patient in a series of 11 HBOT-treated AD patients whose symptomatic improvement is documented with 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18 FDG PET).

Case History

The patient is a 58-year-old, Caucasian female with 5 years of cognitive decline that accelerated 8 months pre-HBOT. Seven months pre-HBOT extensive metabolic, vitamin deficiency, serologic, rheumatologic, imaging, cardiac, and medical evaluations, including apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele testing (homozygous e3) were negative. Electroencephalogram showed diffuse slowing; neuropsychological testing demonstrated multiple cognitive deficits. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was abnormal, suggesting AD (Figure 1). 18 FDG PET imaging 6 months post-SPECT and 1 month pre-HBOT confirmed AD (Additional video 1). Medical history: natural gas inhalation-induced syncope at 8–10 years old (subsequent referral for Special Education), decades’ exposure to metallurgy factory and oil refineries, chronic hypotension, and ten-year work exposure to mold pre-diagnosis. No substance abuse or family history of AD. Brother with dementia secondary to multiple concussions, substance abuse, electroconvulsive therapy. Physical exam: confusion following commands, slight tremor, decreased pinprick diffusely, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, dysdiadochokinesia, finger-to-nose incoordination, and instability on deep knee bend, tandem gait, and Romberg. Patient refused medications except Lexapro and vitamins.

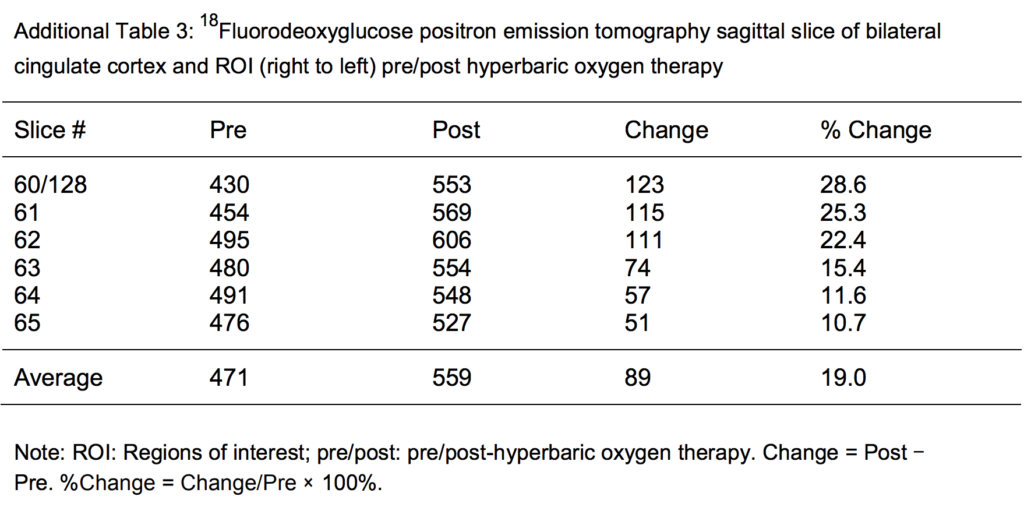

The patient received forty 1.15 atmosphere absolute/50 minutes total treatment time, once per day, 5 days per week, HBOTs in 66 days. After 21 HBOTs the patient reported increased energy/activity level, mood, and ability to draw a correct clock face, perform activities of daily living, and work crossword puzzles. Rivastigmine patch was started and discontinued after one week due to ineffectiveness (patient report). At completion of 40 HBOTs patient reported increased memory and concentration, sleep, conversation, appetite, ability to use the computer, more good days (5/7) than bad days, resolved anxiety, and decreased disorientation and frustration. Tremor, deep knee bend, tandem gain, and motor speed were improved. Repeat 18 FDG PET imaging one month post HBOT showed global 6.5–38% improvement in brain metabolism (Additional Videos 2–6; Additional Tables 1–3). Texture analysis demonstrated a global decrease in the coefficient of variation (CV) except in the Alzheimer’s typical ROIs (Additional Tables 4 and 5). Two months post-HBOT the patient felt a recurrence in her symptoms. She was retreated over the next 20 months with 56 HBOTs (total 96) at the same dose, supplemental oxygen, and medications with stability of her symptoms and Folstein Mini-Mental Status exam (Additional Table 6).

Discussion

AD is a debilitating, costly, rapidly increasing neurological disorder for which there is no effective treatment. 1-3 Etiology is multifactorial, systemic, and immune health-related from insults that occur across the spectrum of life, 13 resulting in reductions of brain regional metabolism. 14 Causes include infection, 13 diabetes mellitus, 13 metabolic disorders, 7 and vascular factors. 15,16 Four pathological processes have been identified 17: vascular hypoperfusion of the brain (and disturbed microcirculation) 18 with associated mitochondrial dysfunction, 6 2) destructive protein inclusions (intracellular neurofibrillary tangles–phosphorylated and aggregated tau protein), and extracellular amyloid plaques, 7 3) uncontrolled oxidative stress, and 4) proinflammatory immune processes 13,19 secondary to microglial and astrocytic dysfunction in the brain. While the vast majority of cases are sporadic, genetic predisposition 20 and epigenetic changes have been implicated. 21 Diagnosis is clinical and can be confirmed with 18 FDG PET hypometabolism in established disease, 22 but is less reliable in mild cognitive impairment. 22-24 Primary treatment is with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors or the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist memantine 5 which have been shown to have positive impact on AD progression 25 with no significant disease-modifying effects. 26 HBOT is an epigenetic 12 modulation of gene expression and suppression 8,9 to treat wounds 9 and disease pathophysiology, 27,28 particularly inflammation. 29 HBOT targets all four of the pathological processes of AD by: 1) affecting the microcirculation 28,30-34 mitochondrial dysfunction 35,36 and biogenesis, 37,38 2) reducing amyloid burden and tau phosphorylation, 39 3) controlling oxidative stress, 40 and 4) reducing inflammation. 29,39,41-43 AD was suggested by SPECT and confirmed after rapid clinical decline by 18FDG PET hypometabolism in the typical temporal-parietal and posterior cingulate areas. 14,22,24 Forty HBOTs improved symptoms and resting global brain metabolism (6.5–38%), including the watershed and posterior cingulate areas. The largest increases were seen in the anterior and mid-cingulate cortices and the least in the posterior cingulate and watershed areas. To our investigation these results are the largest reported global and regional improvements in resting brain metabolism in AD. Test/retest in normal has shown 0.48–9.85% increases in metabolism over 7–23 weeks,44 25 weeks,45 and 17 days,46 while acetylcholinesterase inhibitors treatment has demonstrated regional increases, 47,50 no change, 48 or decreases 47-49 in resting metabolism. The largest increase in global metabolism (26.5%) was seen after 26 weeks of rivastigmine in responders during an activation task, but not in the temporal-parietal watershed or cingulate areas. 51 At the same time, texture results were mixed with a global decrease in CV52 except for the watershed areas which showed the opposite effect. This reduction in CV has corresponded to a visual pattern of smooth texture on SPECT seen in normal individuals and individuals with traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder, 52 carbon monoxide poisoning, 53,54 decompression sickness, 55 near-drowning, 56 and cerebral palsy 56 after both a single HBOT and course of HBOT. It suggests a non-specific global effect on different brain wounding/pathologies. The differential effect on CV and less robust metabolism increases in the watershed regions implies that the patient’s symptomatic improvement may be primarily due to HBOT effects on the rest of the brain. Regardless, HBOT in this patient may be the first drug to not only halt, but temporarily reverse disease progression in AD. In conclusion, a 9-week treatment of low-pressure HBOT (40 sessions) in a patient with AD caused a significant increase in global metabolism on 18 FDG PET imaging with concomitant symptomatic improvement. Mild symptomatic regression was treated with intermittent HBOT, normobaric oxygen, and medications to stabilize symptoms, suggesting the possibility of long-term HBOT treatment of AD with pharmacotherapy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Wilson H. Willie, ARRT (N) (R), for expert acquisition and processing of positron emission tomography images.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the work, definition of intellectual content, literature research, data acquisition, data analysis, manuscript preparation, manuscript editing, and manuscript review: PGH and EFF.

Conflicts of interest

PGH is co-owner of a company that does consulting and renders expert opinions in hyperbaric medicine. EFF is vice-president of the International Hyperbaric Medical Foundation (IHMF), a non-profit corporation that promotes education, research, and teaching in hyperbaric medicine. He derives no income from the IHMF. He also owns a holding company for a mobile hyperbaric clinic named MoPlatte Hyperbarics, LLC.

Financial support

None.

Declaration of patient consent

The author certifies that he did obtain patient consent form. In the form, the patient has given her consent for her images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patient understands that her name and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal her identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Copyright transfer agreement

The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by the authors before publication.

Data sharing statement

Individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article, after deidentification (text, tables, figures, and appendices). Study protocol and informed consent form will be available immediately following publication, without end date. Results will be disseminated through presentations at scientific meetings and/or by publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Anonymized trial data will be available indefinitely at www.figshare.com.

Plagiarism check

Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review

Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Additional files

Additional Video 1: Movie of morphed pre- to post-hyperbaric oxygen therapy 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography single transverse image.

Additional Video 2: Movie of whole brain pre-(left) and post-hyperbaric oxygen therapy (right) 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission to mography transverse images (caudal to cephalad).

Additional Video 3: Movie of pre-(left) and post-hyperbaric oxygen therapy selected 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography transverse images (caudal to cephalad) through temporal-parietal watershed regions of interest.

Additional Video 4: Movie of fused pre- and post-hyperbaric oxygen therapy (left) to post-hyperbaric oxygen therapy (right) 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography coronal slices (anterior to posterior) through the cingulate cortices.

Additional Video 5: Movie of pre-(left) and post-hyperbaric oxygen therapy (right) 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography cingulate cortices sagittal images (right to left).

Additional Video 6: Movie of three-dimensional surface 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography reconstructed images pre-(left) and post-hyperbaric oxygen therapy (right).

Additional Table 1: 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography transverse slice cortical ribbon and posterior temporal-parietal watershed regions of interest (caudal to cephalad) pre/post hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Additional Table 2: 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography coronal slice bilateral cingulate cortices regions of interest (anterior to posterior) pre/post hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Additional Table 3: 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography sagittal slice bilateral cingulate cortex regions of interest (right to left) pre/post hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Additional Table 4: Coefficient of variation in 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography transverse slice cortical ribbon and temporal-parietal watershed regions of interest (right to left) pre/post hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Additional Table 5: Coefficient of variation in 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography coronal slice cingulate cortices (anterior to posterior) pre/post hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Additional Table 6: Post-40 hyperbaric oxygen therapy (after August 2016) clinic course with Folstein Mini-Mental Status Scores

References

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia Statistics. The Global Voice on Dementia. https://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics (last accessed 2018-03-04).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). Alzheimer’s Disease. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/aag/alzheimers.htm (last accessed 2018-12-19)

- World Health Organization. Dementia. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs362/en/ (last accessed 2018-12-19).

- McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263-269.

- Khoury R, Rajamanickam J, Grossberg GT. An update on the safety of current therapies for Alzheimer’s disease: focus on rivastigmine. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2018;9:171-178.

- Onyango IG. Modulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics as a therapeutic strategy in Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13:19-25.

- Frozza RL, Lourenco MV, De Felice FG. Challenges for Alzheimer’s disease therapy: insights from novel mechanisms beyond memory defects. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:37.

- Harch, PG. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for post-concussion syndrome: contradictory conclusions from a study mischaracterized as sham-controlled. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30:1995-1999.

- Harch PG. Hyperbaric oxygen in chronic traumatic brain injury: oxygen, pressure, and gene therapy. Med Gas Res. 2015;5:9.

- Jain KK. In: Jain KK, ed. Chapters 11–13, 18–24, 32, 34, 35, 38, and 42, Textbook of Hyperbaric Medicine, 6th Edition. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017.

- Harch PG. Testimony: “The Impact of Hyperbaric Medicine on Government Health Care, Disability and Education Expenditures.” Hearings, before the Labor, Health and Human Services and Education Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations, United States House of Representatives, One Hundred Seventh Congress, Second Session, Ralph Regula, Ohio, Chairman. Part 7A, Testimony of Members of Congress and Other Interested Individuals and Organizations. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, May 2, 2002. Pps. 589-619.

- Harch PG. Oxygen and pressure epigenetics: understanding hyperbaric oxygen therapy after 355 years as the oldest gene therapy known to man. The Townsend Letter. April, 2018;417:30-34.

- Trempe CL, Lewis TJ. It’s never too early or to late—end the epidemic of Alzheimer’s by preventing or reversing causation from pre-birth to death. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:205.

- Garibotta V, Herholz K, Boccardi M, et al. Clinical validity of brain fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease in the context of a structured 5-phase development framework. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;52:183-195.

- Van der Flier WM, Skoog I, Schneider JA, et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1-16.

- De la Torre J. The vascular hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: a key to preclinical prediction of dementia using neuroimaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63:35-52.

- Weinstein JD. A new direction for Alzheimer’s research. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13:190-193.

- De la Torre JC, Mussivand T. Can disturbed brain microcirculation cause Alzheimer’s disease? Neurol Res. 1993;15:146-53.

- Salinaro AT, Pennisi M, Di Paola R, et al. Neuroinflammation and neurohormesis in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer-linked pathologies: modulation by nutritional mushrooms. Immun Ageing. 2018;15:8.

- Bis JC, Jian X, Kunkle BW, et al. Whole exome sequencing study identifies novel rare and common Alzheimer’s-Associated variants involved in immune response and transcriptional regulation. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0112-7.

- Nativio R, Donahue G, Berson A, et al. Dysregulation of the epigenetic landscape of normal aging in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:497-505.

- Rice L, Bisdas S. The diagnostic value of FDG and amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s disease-A systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2017;94:16-24.

- Smailagic N, Vacante M, Hyde C, Martin S, Ukoumunne O, Sachpekidis C. 18F-FDG PET for the early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD010632.

- Promteangtrong C, Kolber M, Ramchandra P, et al. Multimodality Imaging Approaches in Alzheimer’s disease. Part II: 1H MR spectroscopy, FDG PET and Amyloid PET. Dement Neuropsychol. 2015;9:330-342.

- Rountree SD, Chan W, Pavlik VN, Darby EJ, Siddiqui S, Doody RS. Persistent treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and/or memantine slows clinical progression of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2009;1:7.

- Patel L, Grossberg GT. Combination Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:539-546.

- Harch PG, Neubauer RA. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in Global Cerebral Ischemia/Anoxia and Coma. In: Jain KK, ed. Chapter 18, Textbook of Hyperbaric Medicine, 3rd Revised Edition. Gottingen, Germany: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers; 1999:319-349.

- Weaver, LK, editor. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Indications. The Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Committee Report, 13th ed. Durham, NC: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society: 2014.

- Rossignol DA. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy might improve certain pathophysiological findings in autism. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:1208-1227.

- Marx RE, Ehler WJ, Tayapongsak P, Pierce LW. Relationship of oxygen dose to angiogenesis induction in irradiated tissue. Am J Surg. 1990;160:519-524.

- Harch PG, Kriedt C, Van Meter KW, Sutherland RJ. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves spatial learning and memory in a rat model of chronic traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2007;1174:120- 129.

- Manson PN, Im MJ, Myers RA, Hoopes JE. Improved capillaries by hyperbaric oxygen in skin flaps. Surg Forum.1980;31:564-566

- Bilic I, Petri NM, Bezic J, et al. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen therapy on experimental burn wound healing in rats: a randomized controlled study. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2005;32:1-9.

- Lin KC, Niu KC, Tsai KJ, et al. Attenuating inflammation but stimulating both angiogenesis and neurogenesis using hyperbaric oxygen in rats with traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:650-659.

- Niu CC, Lin SS, Yuan LJ, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment suppresses MAPK signaling and mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in degenerated human intervertebral disc cells. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:204-209.

- Dave KR, Prado R, Busto R, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy protects against mitochondrial dysfunction and delays onset of motor neuron disease in Wobbler mice. Neuroscience. 2003;120:113-120.

- Suzuki J. Endurance performance is enhanced by intermittent hyperbaric exposure via up-regulation of proteins involved in mitochondrial biogenesis in mice. Physiol Rep. 2017;5: e13349.

- Gutsaeva DR, Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Demchenko IT, Piantadosi CA. Oxygen-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2006;137:493-504.

- Shapira R, Solomon B, Efrati S, Frenkel D, Ashery U. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy ameliorates pathophysiology of 3xTg-AD mouse model by attenuating neuroinflammation. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;62:105-119.

- Simsek K, Sadir S, Oter S. The relation of hyperbaric oxygen with oxidative stress-reactive molecules in action. Oxid Antioxid Med Sci. 2015;4:17-22.

- Godman CA, Chheda KP, Hightower LE, Perdrizet G, Shin DG, Giardina C. Hyperbaric oxygen induces a cytoprotective and angiogenic response in human microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15:431-442.

- Kendall AC, Whatmore JL, Harries LW, Winyard PG, Eggleton P, Smerdon GR. Different oxygen treatment pressures alter inflammatory gene expression in human endothelial cells. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2013;40:115-123.

- Chen Y, Nadi NS, Chavko M, Auker CR, McCarron RM. Microarray analysis of gene expression in rat cortical neurons exposed to hyperbaric air and oxygen. Neurochem Res. 2009;34:1047-1056.

- Gur RE, Resnick SM, Gur RC, Alavi A, Caroff S, Kushner M, Reivich M. Regional Brain Function in Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:126-129.

- Shaefer SM, Abercrombie HC, Lindgren KA, Larson CL, Ward RT, Oakes TR, Holden JE, Perlman SB, Turski PA, Davidson RJ. Six-month test-retest reliability of MRI-defined PET measures of regional cerebral glucose metabolic rate in selected subcortical structures. Hum Brain Mapping. 2000;10:1-9.

- Sundar LKS, Muzik O, Rischka L, et al. Towards quantitative [18F]FDG-PET/MRI of the brain: Automated MR-driven calculation of an image-derived input function for the non-invasive determination of cerebral glucose metabolic rates. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2018:271678X18776820.

- Teipel SJ, Drzezga A, Bartenstein P, Moller HJ, Schwaiger M, Hampel H. Effects of donepezil on cortical metabolic response to activation during 18FDG-PET in Alzheimer’s disease: a doubleblind cross-over trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;187:86- 94.

- Tune L, Tiseo PJ, Ieni J, et al. Donepezil HCl (E2020) maintains functional brain activity in patients with Alzheimer disease: results of a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11:169-177.

- Mega MS, Dinov ID, Porter V, et al. Metabolic patterns associated with the clinical response to galantamine therapy: a fludeoxyglucose f 18 positron emission tomographic study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:721-728.

- Stefanova E, Wall A, Almkvist O, et al. Longitudinal PET evaluation of cerebral glucose metabolism in rivastigmine treated patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2006;113:205-218.

- Potkin SG, Anand R, Fleming K, et al. Brain metabolic and clinical effects of rivastigmine in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;4:223-230.

- Harch PG, Andrews SR, Fogarty EF, Lucarini J, Van Meter KW. Case control study: hyperbaric oxygen treatment of mild traumatic brain injury persistent post-concussion syndrome and post-traumatic stress disorder. Med Gas Res. 2017;7:156-174.

- Harch PG, Van Meter KW, Neubauer RA, and Gottlieb SF. Use of HMPAO SPECT for assessment of response to HBO in ischemic/ hypoxic encephalopathies. In: Jain KK, ed. Appendix, Textbook of Hyperbaric Medicine, 2nd Edition. Gottingen, Germany: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers; 1996:480-491.

- Van Meter KW, Harch PG, Andrews LC, et al. Should the pressure be off or on in the use of oxygen in the treatment of carbon monoxide-poisoned patients? Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:283-288.

- Barratt DM, Harch PG, Van Meter K. Decompression illness in divers: a review of the literature. Neurologist. 2002;8:186-202.

- Harch PG, Neubauer RA. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in global cerebral ischemia/anoxia and coma. In: Jain KK, ed. Chapter 18, Textbook of Hyperbaric Medicine, 3rd Revised Edition. Gottingen, Germany: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers; 1999:319-345.